'B' is for Berger: Meeting Evil Neighbors with Empathy & Eloquence

I owe a debt to many writers, such as Donald E. Westlake, Flannery O' Connor, George V. Higgins, and Shane Stevens … but I owe an incalculable sum to the writings of Thomas Berger.

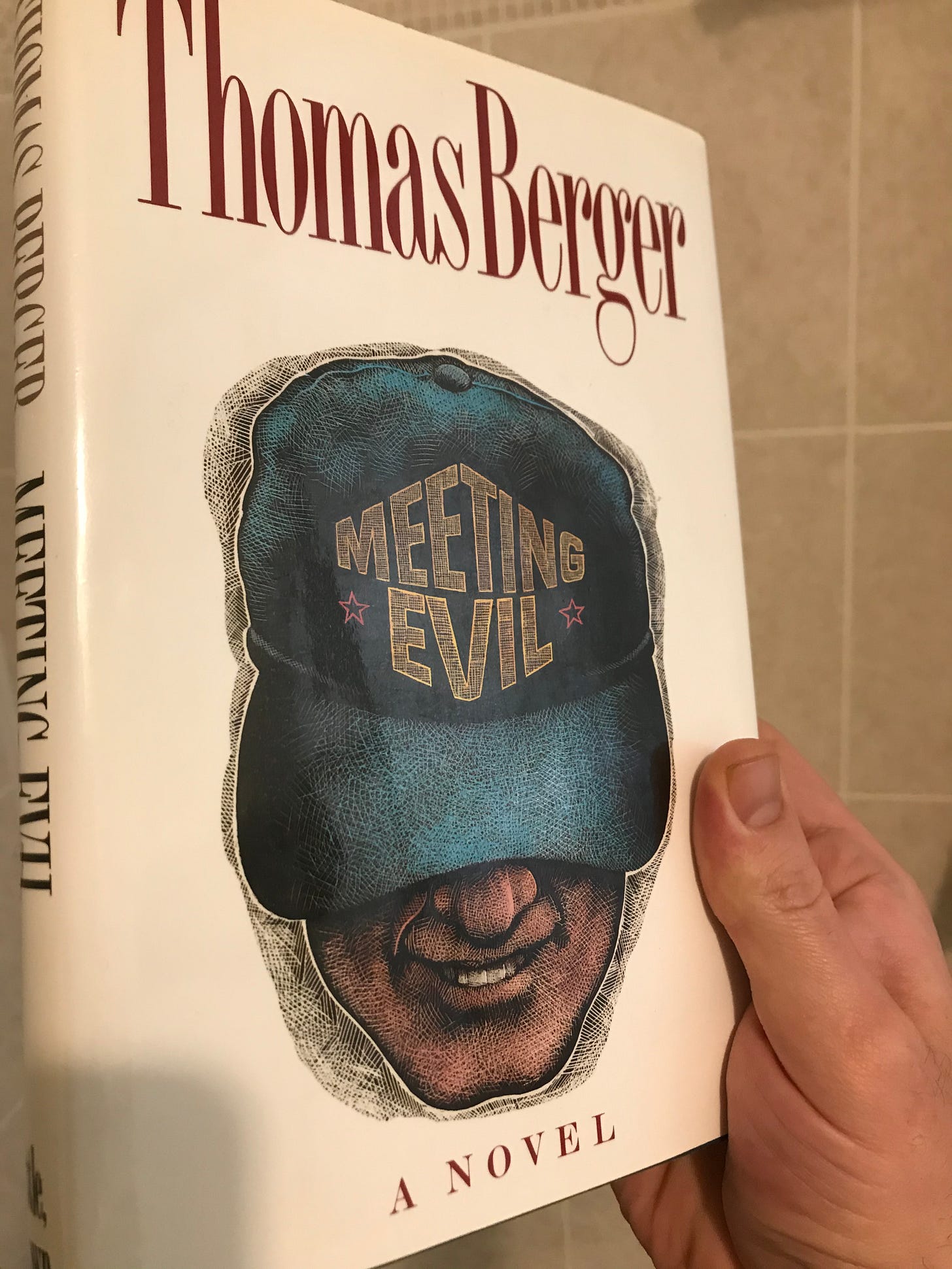

My wife got me a rare hardcover edition of Thomas Berger's Meeting Evil for the holidays, and it was almost the greatest gift she could have gotten me (I say almost because she got me another book as well, which I'll talk about in my next post). It was such an excellent surprise because it truly is the gift that will keep on giving. I know this because that has been my experience with Thomas Berger's work, especially his 1980 novel Neighbors.

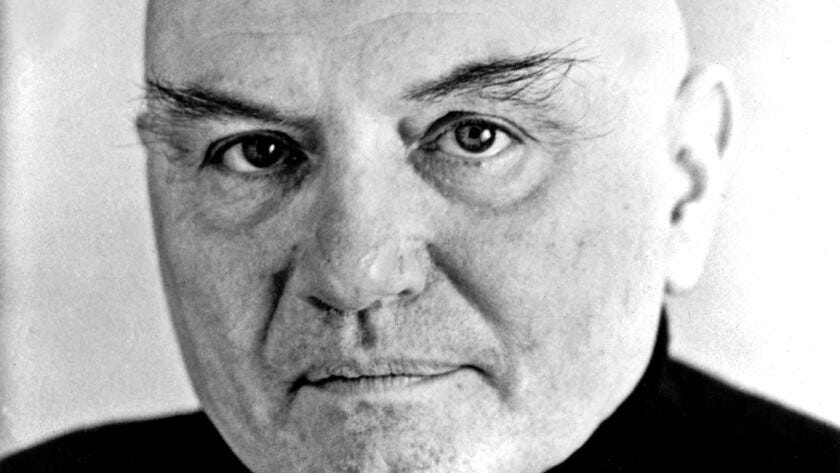

I was in my teens when I first discovered the arcane luster of Thomas Berger's writing. Watching Neighbors with my brother is an experience I'll never forget, but it paled in comparison to finding Berger. Opening the pages of Neighbors, the novel, was like stumbling across a secret treasure chest of linguistic magic. Berger loved language on a level of reverence few modern authors have exhibited.

I owe a debt to many writers, such as Donald E. Westlake, Flannery O' Connor, George V. Higgins, and Shane Stevens … but I owe an incalculable sum to the writings of Thomas Berger. The way he bent language to his will enthralled me to such a degree that I grew to worship the written word. I remember the discovery with particular fondness.

The movie Neighbors—the one with John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd—had come to television and my whole family loved it. I must come from a long line of weirdos because my family has always had a potent affinity for the strange movies that bombed at the box office (Hudson Hawk, Nothing but Trouble, Very Bad Things) after being eviscerated by clueless newspaper critics. Neighbors was no exception.

My brother and I were frequently doubled over and laughing our guts out by the time Belushi's beleaguered Earl Keese gets locked in his own basement and Aykroyd's Vic is on the phone with him, pretending to be some sort of demon. This was our kind of Bizarro before Bizarro was a thing.

Keese finds himself locked in his own basement, being deceived by his new neighbor who is standing in Keese's kitchen, actively mocking him over his own phone. The concept was so anachronistic it was hilarious. If there is one thing that the film adaptation shares with its source material it is the absurdity of modern living and here Earl Keese's territoriality is perverted to the point of hysteria, as his own home is used against him.

The more we watched the movie and laughed, the more I needed to know who wrote it. That's when I started digging through newspaper articles about the flick and discovered how much everyone else seemed to despise it. The critics ripped on everything from Belushi and Aykroyd's decision to reverse roles to the producers' choice of theremin music to score the movie. Some thought the problem was Belushi, while others laid the blame on the lame direction of John G. Avildsen (The Karate Kid, Lean on Me, Rocky V), but most everyone agreed that the film was a grave insult to its source material, a book they described as something of a minor masterpiece.

When I finally got my hands on Neighbors I was taken not only with the accuracy of those honest if cruel film reviews but, also, with the language of its author. Here was a Cincinnati-born novelist who could manage, during the course of a single paragraph, to sound like both a poorly educated lower-middle class pencil pusher and a senior proctor at Oxford University. Neighbors was, indeed, a minor masterpiece, but it took me a long time to realize it ... because it took me a long time to read it.

To be clear, Neighbors is not a long novel. As a matter of fact, it would be considered by some to be rather short at just under three hundred pages. And Thomas Berger is not a boring writer by any stretch. No. The reason it took me so long to finish reading Neighbors owes to the irresistible language that Berger employs. Not since the imagistic flights of Burroughs' Naked Lunch had I paid so much attention to every single word in a sentence, studying it, relishing in it, and repeating it to myself.

The term “wordsmith” is often hurled around literary circles at virtually every person who was ever fortunate enough to put pen to paper or, more literally, fingertips to keyboard. In light of how carelessly this term is used there should exist another word to describe people like Thomas Berger, who wield the English language with such skill, discipline, and humor.

Every author has their own cloistered lexicon, a small pillowcase full of words that they return to again and again, often involuntarily or unconsciously. For Berger, the word he returned to the most was “exhortation.” The word appears multiple times throughout his body of work.

In Neighbors, he writes of the misfit Ramona, “'Pride of possession.' She enunciated this as a thing-in-itself, as a term to be displayed on a license plate by way of state motto or tourist-exhortation.”

Twelve years later, he returns to the word yet again in Meeting Evil, writing, “Joanie had lately given up the habit: she had at last been scared off by a series of antismoking exhortations on television.”

Many writers use words with reckless disregard, neither fully comprehending their meaning nor properly conveying the same. Others manipulate language to buttress their agenda or ideological point. Berger never did any of that. Rather, he used language consummately, whether he was using it literally (as he always did the word “exhortation”) or figuratively (in the mouths of his characters).

In fact, some of his best works were both pristinely written and thematically consumed by characters for whom language is a primeval and misunderstood tool. Consider Earl Keese, the protagonist of Neighbors, who thinks to himself, “How could his privates be shameful if he had been born with them willy-nilly?”

On the one hand, this musing makes the reader laugh because of Berger's choice of an inherently silly-sounding phrase (willy-nilly), one that is frequently used in everyday speech as a surrogate for the haphazard. On the other hand, Berger is using willy-nilly in the literal sense (“whether one likes it or not”), which gives this musing a noirish implication. This is what makes Berger such a singular author—his commanding ability to be witty and existential in the same sentence.

As I read this back, I can see why Berger's readership remains so small and scattered, and why mainstream mass market paperback success may have eluded him. To try and describe his work is to misrepresent him as a haughty and unapproachable talent, one prone to grandiloquent language and pompous characterization. The truth is quite the opposite.

The protagonist of Meeting Evil is an average everyday dude, as is Earl Keese in Neighbors, and so, too, is Russel Wren, the schlubby anti-hero of Berger's sordid hard-boiled crime novel Who is Teddy Villanova? Despite the misconception, perpetuated by his sadomasochistic Reinhart franchise, Berger's command of language is never employed to express derision but to fondly satirize the familiar. This language is employed almost acrobatically in service of the absurd and nowhere is this more effective than it is in Neighbors, a book that differs dramatically from its cinematic counterpart.

In Neighbors: The Movie, Earl Keese gets into what is likely the first mano a mano scuffle of his adult life and ends up mired in some dark marshland variation of quicksand, nearly drowning until he is saved, at the last minute, by his strange and combative new neighbor (Dan Aykroyd). As the neighbor is pulling him out of the mire, thus saving his life, Keese decides to escalate the fight they had already been having by jerking violently on the implement the neighbor was using to save him. This sends the neighbor into the muck where he drowns … or so Keese thinks.

We later learn that the neighbor survived this affront, but how he survived is never clearly or convincingly explained. It is even suggested, at one point, that this may have all been a practical joke that was planned in advance with the amused participation of Keese's wife, Enid.

I tell you all of this not to spoil the plot or criticize the movie, but strictly to draw a line between the book and its film adaptation. The events I described above are nowhere to be found in Berger's novel, at least not in such crude and cartoonish ways. Nor is the character Vic in attendance. Where Aykroyd's wiry dead-toothed Albino exists on screen there is a stout and hirsute man named Harry on the page, one whose size is described in terms far more intimidating than any of Aykroyd's facial bluster.

The antics of the film are lensed in such a way as to feel right at home in one of the lesser horror titles of the Poverty Row era or, maybe, early Roger Corman. Much of the film is set up like a weird home invasion movie … where the homeowner invites the invaders in and then buys them dinner, bitching about having to pay every step of the way. It's funny, sure, but severely askew, and very rarely indebted to the book that inspired it.

By contrast, the pseudo-macho scuffle of Berger's Neighbors leads to a spill down a steep but grassy hill, into marshland, where the worst offense committed is a boot on Keese's back and Vic sticking Keese's face into mud pie. There is no quicksand, nor is there any real brush with death. However, the book is far more effective and much funnier at flirting with the Reaper in all its cloaked and cuckoo ambiguity:

“Push me again,” said Keese, “and you'll be sorry.”

“Huh?”

“You know what I mean.”

“Search me!” Harry almost wailed. He was truly shameless. “I'll show you, then,” Keese said, and bulky as he was, he found enough room on the beaten part of the path to stand aside. He then gestured, with sweeping hand, for Harry to precede him and gave him plenty of light. When Harry gullibly obeyed, Keese struck him in the small of the back. The larger man lost control of his stride and went hurtling down the path. Suddenly, horribly, he vanished from view, as if a precipice had opened before him and he had gone helplessly over its edge. A brief and terrible cry was heard, which faded away below Keese's feet, and then the utter silence of vegetable nature on a windless night.

As if destroying Keese's car had not been enough, he had now killed the man! It was new in Keese's experience (of almost fifty years) for things to get so completely out-of-hand. His instinct was to turn and escape, hasten to the city, buy a ticket to some remote part of the world, and hide out there forever, living by the proceeds of some depraved trade in flesh or drugs.

This portion of the story shows us how Earl Keese's deluded mind works and how fast he surrenders any semblance of rational thinking. The comedy is in his utter lack of scruples, comparing something as petty as car damage to the presumed death of the neighbor responsible for that damage. It is also in the outlandish plan he hatches on the spot, a plan without any sense of reality about it.

Which brings us to why Neighbors the book has outlasted Neighbors: The Movie. Where the flick concerns itself almost exclusively with the basest urges of middle class married men (the real or imagined advancements of a sultry stranger, the animal-like territoriality of such men, and the paranoid, even infantile tantrums of those men), the book focuses more astutely on the inner workings of that man's mind.

Neighbors: The Movie captures madness, insofar as it knocks the idea of paranoia around like a cat batting its prey about the face, but its portrait of madness is nothing compared to the words of its true creator. In his book, Berger establishes paranoia as the reigning mentality from the very first page:

While passing through the dining room, which was papered in pale-gold figure, he bent slightly so that he could see, under the long valance and over the window-mounted greenhouse, into the yard next door. Despite what he believed he saw he did not break his stride. In the kitchen he looked again: it was a large white dog, in fact a wolfhound, not a naked human being on all fours.

Were Keese to accept the literal witness of his eyes, his life would have been of quite another character, perhaps catastrophic, for outlandish illusions were, if not habitual with him, then at least none too rare for that sort of thing. Perhaps a half-dozen times a year he thought he had such phenomena as George Washington urinating against the wheel of a parked car (actually an old lady bent over a cane), a nun run amok in the middle of an intersection (policeman directing traffic), a rat of record proportions (an abandoned football), or a brazen pervert blowing him a kiss from the rear window of a bus (side of sleeping workingman's face, propped on hand).

This opening portrait of Keese's askew visions colors the entire novel, bringing a sense of real suspense to even the most amusingly bonkers scenario. For example, Keese at one point vehemently denies he's made any sexual advances toward Harry's partner-in-crime, the come-hither Ramona, but Enid turns around and insists that her husband was trying to sexual assault Harry, a man more than twice his size. While this sounds admittedly grim, the back-and-forth tells us everything we need to know about Earl and Enid's marriage, Enid's opinion of her husband, and Earl's expectations of infidelity.

This is where the film adaptation of Neighbors fails to pay homage to Berger and his gifts. If the book is paranoid and psychotic the film goes in mostly for the psychotic part, and only for the sake of laughs. Berger's brand of satire has often been referred to as “anarchic,” which may explain the appeal it held for John Belushi. At the time, the Saturday Night Live star had become infatuated with the punk rock scene, particularly the music of heavier acts like Fear whose stage act was all about the spirit of anarchy.

What reviewers miss about Berger's satire is the depth of feeling that he has for his protagonists, regardless of their idiosyncrasies or inadequacies. Even Reinhart, arguably his most famous and infamous creation, receives a degree of empathy that is rarely glimpsed in the ironic prose of post-modern novelists.

This empathy is something the cast and crew of Neighbors: The Movie did their best to mimic, but the result was less than convincing. In retrospect, the way in which Belushi's Keese blows hot and cold with his new neighbors is downright pathological, but it is pathological without the benefit of the novel's look into Keese's psyche. The film gives viewers no clues about why Keese behaves the way that he does nor how his neighbors' actions might not be as they seem. This makes his sudden embrace of the crazy kids next door all the more jarring and unrealistic.

If there is one thing that the film has in common with its author, it is the cynicism that supposedly came to dominate Berger's hermetic existence in his final years. You'd be cynical too, if you wrote more than twenty-two novels, only to have your work fall into relative obscurity.

Nevertheless, Berger didn't write with a cynical quill. Instead, he wrote from a self-professed love. In the author's own words, “What results is the best I can manage by way of joyful worship—not the worst in sneering derision.”

It is Berger's empathy, language, and wit that make receiving one of his books such a wonderful gift. I haven't read all of Meeting Evil yet (though I have seen the ill-received movie adaptation, starring Luke Wilson and Samuel L. Jackson), but I know it's a gift that I will treasure for years to come. Because it will take me at least that long to read it all the way through, pausing frequently to hang on every word and savor each of Berger's sumptuously written sentences.

Bob Freville is an author and filmmaker from New York. He is the writer-director of the Berkeley TV cult classic Of Bitches & Hounds and the Troma vampire drama Hemo. Freville is the author of Battering the Stem, The Network People, and The Proud & the Dumb. His work has been published by Akashic Books, Bizarro Central, Horror Sleaze Trash, Psychedelic Horror Press, Scary Dairy Press, and more. Follow him at @bobfreville.