Beneath the Current of Our Existence: On Miguel de Unamuno's Niebla

Unamuno referred to his characters as agonists, which is apt given the plight they endure.

Unamuno's most notorious “nivola” (a term coined by Unamuno to describe a work shorter than a novel and longer than a traditional novella), Niebla, AKA 'Mist,' AKA 'Fog,' is a work that largely eluded an English-speaking audience until the dawn of the twenty-first century. The book, written in 1907 and first published in 1914, concerns an introverted intellectual who falls for the wrong woman, only to discover that his significant wealth cannot buy her love. It is also, arguably, a philosophical treatise on Creationism, Christianity, Simulation hypothesis, and the right to die by one's own hand.

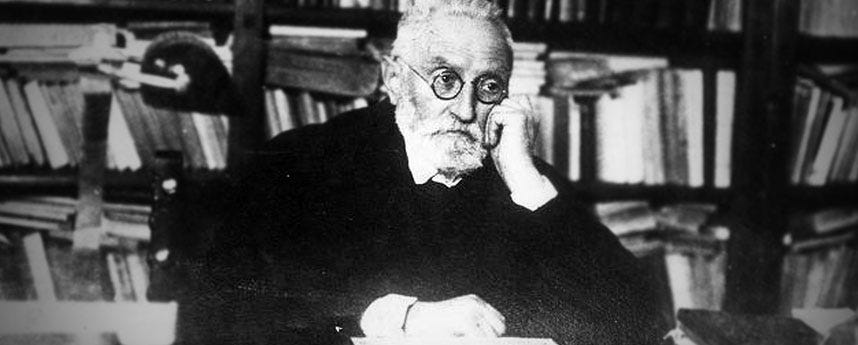

This is a book by Miguel de Unamuno and anyone familiar with the late Spanish essayist can tell you, that means it is a psychic stew. Whether writing of Cervantes' crowning creation, Don Quixote, or the agony of Christendom, the infamous rector is impassioned, distracted, and all over the place. He is also on fire, on point, and knows exactly where he is going, whether he realizes it or not.

At the start of Niebla, we find the male suitor Augusto standing at the door of his house, his body fixed in an "august and statuesque attitude." He does not seem capable of moving of his own accord or making his own decisions; his only choice is to wait for a dog to pass, resolving to follow the dog in whatever direction it takes him.

This motionlessness will be familiar to many modern readers from hours spent playing video games like The Sims, games that some believe mirror our own real-life existence, but there is more at work here than mere Musk-style simulation theory. Unamuno is laying the groundwork for a meditation on creation and creators, on self-actualization and self-immolation, and the result is a conglomeration of thought that should be of intellectual and emotional sustenance to everyone from lapsed Catholics to dyed in the wool atheists.

We have all, at one point in our lives or another, indulged in the idea that something, some force, is at work, and that this malevolent anima mundi is working against us instead of to our advantage. The shrinks call such thinking an “external locust of control,” while Lovecraft agnostics likely imagine it a conspiracy by a many-tentacled and ancient merman. For some of us it is simply a way to blame someone else in the moment; it is no more nor less than the blame we lay on a boyfriend or girlfriend when we stub our own toes by walking blindly through a room (“Why do you have to leave your fucking shoes in the middle of the floor?”). Nevertheless, Unamuno handles the subject with self-effacing wit and a guileless desire to understand the human tragedy or tragicomedy, if you prefer.

It is well-known — among that handful of Westerners familiar with his work — that Unamuno was inspired to write Niebla after reading Søren Kierkegaard's Diary of a Seducer. The philosophical debt Unamuno owed to Kierkegaard has never gone unacknowledged, least of all by Unamuno himself who admitted to teaching himself Danish in order to read the theologian's original texts. However, the influence of the so-called first existentialist runs deeper than one might initially think.

Yes, Niebla is a story about love (“love is the child of illusion and the parent of disillusion.”) and man's obsession with a woman, but the story shares less in common with Kierkegaard's Diary of a Seducer – a work by a strange young man who equates momentary erotic enjoyment with rape - and more with the Dane's overall ethos.

Kierkegaard famously said, “The function of prayer is not to influence God, but rather to change the nature of the one who prays.”

In Niebla, Unamuno writes, “No, it's not that he looked at me, it's that he wrapped me in his gaze; and it is not that I believed in God, but that I believed myself a god.”

Kierkegaard also said, “Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.”

To which Unamuno might add, “Beneath the current of our existence and within it, there is another current flowing in the opposite direction. In this life we go from yesterday to tomorrow, but there we go from tomorrow to yesterday. The web of life is being woven and unraveled at the same time. And from time to time we get breaths and vapors and even mysterious murmurs from that other world, from that interior of our own world.”

In fact, the only thing that Unamuno can truly be accused of lifting from Diary of a Seducer is the central concept of “mist” from which Niebla gets its English title.

Kierkegaard writes, “I, Too, am carried along into the kingdom of mist, into that dreamland where one is frightened by one's own shadow at every moment.”

To which Unamuno responds, in the voice of a dog confronted by his master's interment, “I feel my own soul becoming purified by this contact with death, with this purification of my master. I feel it mounting upward towards the mist into which he at last was dissolved, the mist from which he sprang and to which he returned.”

It is this mist – the great chasm of unknown and plausible nothing and uncharted and possible everything – which is the true subject of Unamuno's novel and, indeed, his entire oeuvre. On the surface, Niebla is a forerunner of Maugham's Of Human Bondage, but these two works differ dramatically, as well. For one, W. Somerset Maugham's novel is closer in size to the Bible, even if Niebla is closer in scope. Both novels share a hopeless male lead and an unfortunate cross-section of lovers, but that is, more or less, where the comparison ends.

Like that tragic sense of life experienced by man upon his conception, Niebla is also funny, disordered, excruciating, profound and, in the end, painfully short. The same cannot be said of Maugham's beautifully worded but staggeringly protracted saga of a man with a club foot and a lonely heart.

If Kierkegaard's aforementioned remarks about rape seem antiquated and wholly bizarre, Unamuno's text isn't without its own outmoded beliefs; a character says, “I have too much body because I lack soul,” which can be read as a comment on obesity just as easily as it can be seen as a metaphor for spiritual bankruptcy. His thoughts on the necessity of marriage and propagation are even more vexing (“Marry the woman who loves you, even if you don't want her. It is better to marry so that they can conquer one's love.”) and serve as the linchpin in Niebla's thin plot.

Unamuno referred to his characters as agonists, which is apt given the plight they endure. Augusto, Niebla's male fulcrum and love's foil, is heartbroken when his Dulcinea by a different name, Eugenia, runs off with her lover Mauricio. In turn, Mauricio's former lover Rosario has her heart broken by Augusto. Each of these characters possesses the capacity for suffering and for causing others to suffer.

Enter into this tragicomic melodrama the author himself in a stroke of metafiction that predates the emergence of postmodernism by nearly fifty years — Unamuno the Author intervenes in Augusto's suicide attempt, informing his central agonist of his fictitiousness and insisting that a figment of the imagination does not have such luxuries as the right to die.

When faced with this cruel denial of liberty, Augusto takes to gorging himself, which slowly kills him over time. After “learning” of his agonist's unfortunate passing, the author is visited by that fictional agonist in a dream. This appearance of the dead suggests both Jesus and Lazarus in its evocation of the Second Coming or rising of the spirit, which makes sense when one considers the point that is being made here.

Early in the book, Augusto says, “Here, in this wretched life, we think only of putting God to use.” The line carries a lot of weight, as it suggests that man invented God so that he may feel more like a god (a puppet master, pulling the strings) himself. This concept is pushed to its limit with the arrival of Unamuno the Author, a character in his own right who attempts to exert his will over his creations, only to discover that they have a will of their own, for good or ill.

If Augusto seems, at first, to be a marionette driven by some other force it is suitable that Niebla should end in a place that is the obverse of where it started - with the author confined to dreaming of the creation he could not control and his subject shuffling loose the mortal coil that has caused him such anguish.

It is the final chapter, 'Funeral Oration By Way of an Epilogue,' which makes plain what Unamuno has been trying to convey over the last three hundred twenty-odd pages of his “nivola.” Written by Orfeo, the decedent's embittered pet dog, the passage reads, “'What a strange animal is man! His mind is never where it ought to be, namely, where he is himself; he talks in order to lie; and he wears clothes!

“'Poor master! Within a short time they will bury him in a place set apart for the purpose. Men preserve and store up their dead, and they refuse to allow the dogs and the crows to eat them! To what purpose? That there may be left of them at last only what every animal, beginning with man himself, leaves in the world, namely, a few bones. They store up their dead! An animal that speaks, wears clothes, and stores up his dead! Poor man!'”

This being the age of spoiler alerts, one could be forgiven for thinking that I have given up the ghost by revealing so much of Niebla's plot and denouement, but I assure you, I have barely scratched the surface. This is an Unamuno and, like the man who created it, this Unamuno contains multitudes.

If you took something from this exploration of Niebla, please consider subscribing to my newsletter (it's FREE!!!) and be sure to keep an eye on my Substack for future updates.