On the Fly and Losing Time: Encouraging Monsters with Paul Hibbard, Director of the Home Invasion Thriller “Some Visitors“

St. Louis director Paul Hibbard explains why Home Alone is a gateway drug to home invasion horror, while breaking down the making of his unsettling new film.

The home invasion film has always been a subgenre of particular interest to me. Part of that fascination stems from my own anxiety, which itself stems from my history of being stalked, sexually abused, and stranded in the middle of nowhere. It isn't a part of my life that I have ever publicly acknowledged, except, perhaps, in social media posts warning friends about the name of my stalker.

I should clarify here that my stalker was not one of the people who sexually abused me, nor did my stalker or rapist leave me stranded in the middle of nowhere. These were all separate events occurring over the course of 10+ years, which serves to illustrate just how common these unfortunate events really are.

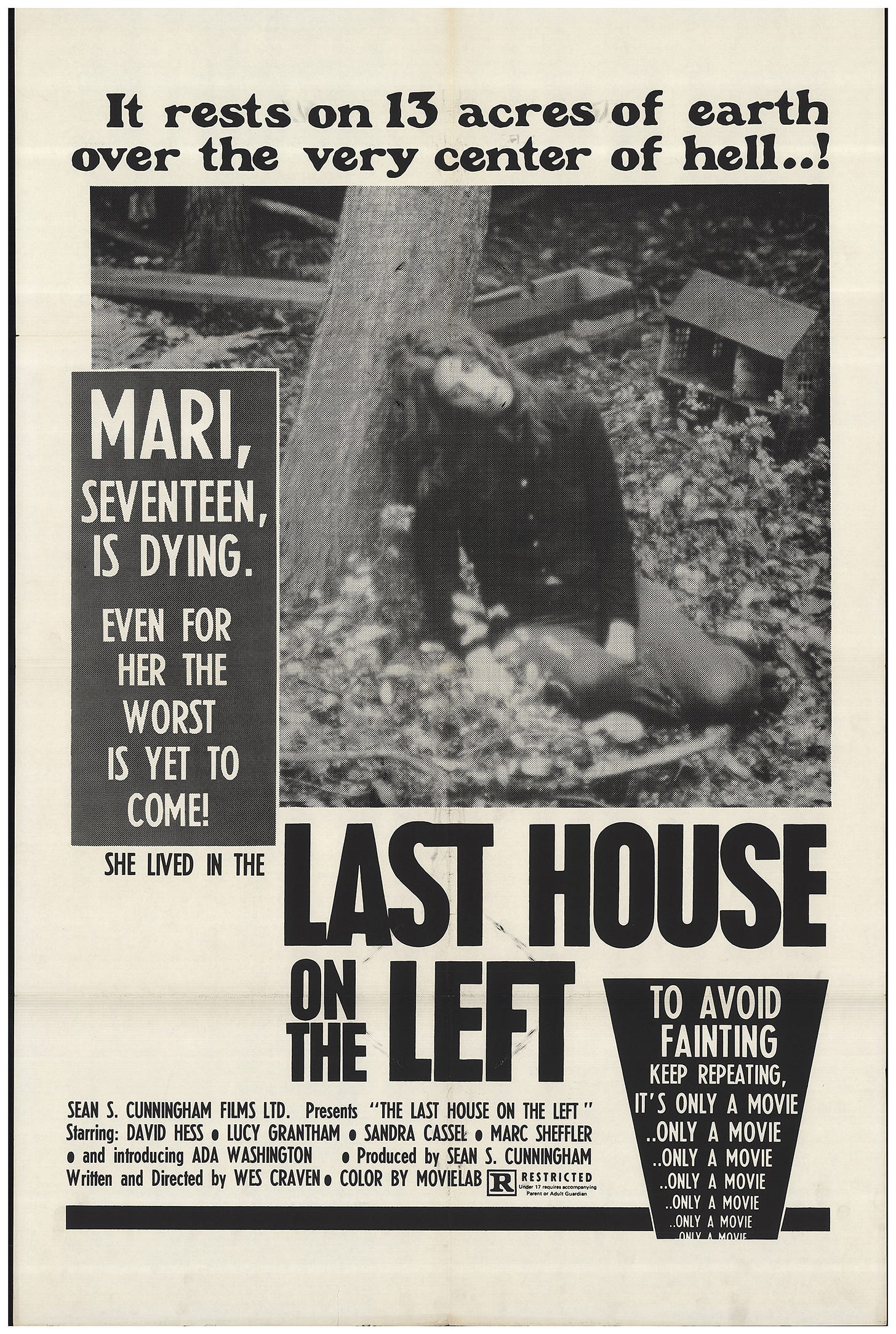

When we are growing up, we are told that monsters aren't real, that what we see in movies and read in books cannot actually hurt us. Some of us even grow up surrounded by deliberately charged movie advertising like that of 1972's The Last House on the Left – the proto-home invasion film that some might say started it all – whose poster nevertheless assured us, “... it's only a movie... it's only a movie... it's only a movie.”

Except, it's not. As St. Louis filmmaker Paul Hibbard's award-winning home invasion short Some Visitors reminds us in its opening title card, there are over two million home invasions in the United States every year. One occurs every 26 seconds. And intruders typically target locations that look like someone is home.

These stats don't surprise me, the frequency with which home invasions occur seems to align with what I know from my own life experiences. Bad shit is happening every moment of every day, while you're awake and while you're asleep. When you're counting sheep, someone else is getting their throat slit. Others are getting raped, ripped off, beaten, or otherwise broken by their neighbors or strangers.

What seems surprising is the tendency toward occupied houses. The media regularly feeds us a steady diet of degradation, an amount sufficient to make any halfway cognizant individual well-aware of how rampant crime is in this country and most others. But when one thinks about break-ins, one takes for granted that most criminals would want to get in and out.

You'd be forgiven for thinking that most criminals would prefer to hit homes that are unoccupied or otherwise deserted. According to The National Institute of Justice Drug Use Forecasting Program, 58% of males charged with stolen property tested positive for drug use, while 48% of those charged with assault tested positive for the same. If your crime is motivated by drug addiction, you would think you'd want as few obstacles between you and your next fix as possible.

On the contrary, 27.6% of home invasions occur when someone is home, and 36% of home burglary victims sustained minor injury or psychological trauma. Media outlets, particularly banking, travel, and real estate publications, like to cite the fact that only about seven percent of home invasions involve violence, but they ignore how significant that number actually is.

If we use a recent example, there were an estimated 1,117,696 burglaries in 2019. If you do the math, that's approximately 78,238 violent assaults in the U.S. alone. The figure may seem small, especially given how many people live in America, but the number doesn't seem so small when you find yourself alone in a location where there isn't a neighbor in the world who would respond to your hypothetical cries of distress.

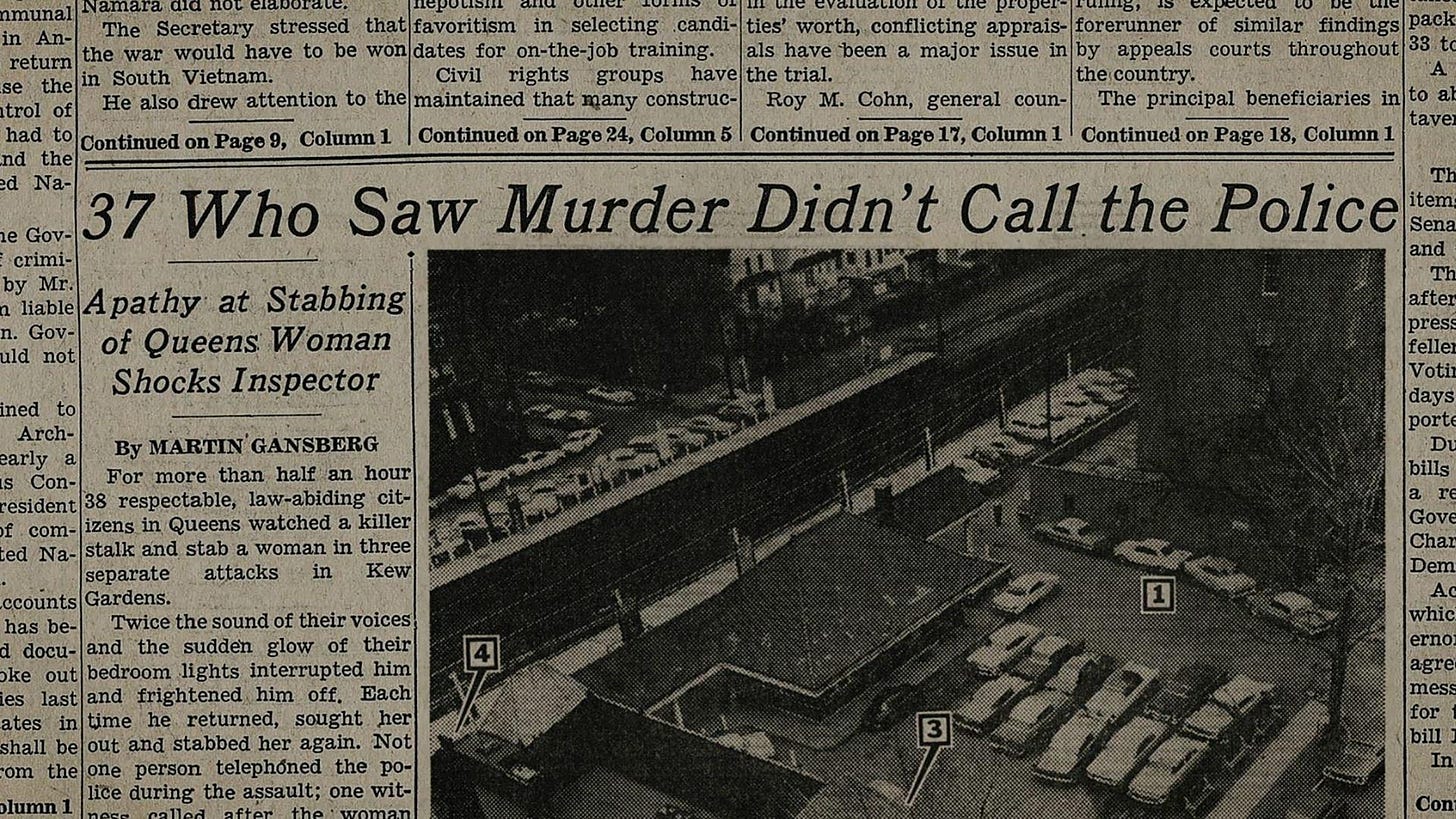

The modern world is a jaded one and people aren't taking any chances. Kitty Genovese lived in one of the most populated neighborhoods in one of the most densely populated cities in America. She rented an apartment in a building that housed throngs of Kew Gardens residents. At least 37 of her neighbors watched as she was raped and then stabbed in the lung in the alley behind the place they all called home. Not a single one of them called the cops.

The home invasion film was most certainly born out of the cynicism of the Vietnam era, but it endures to this day for the same reason that no one opened their doors for the 28-year-old barmaid from Kew Gardens – because we're all wary of what awaits us on the other side of that door. It's not a mistake that Ring sold 1.4 million of its video doorbells in 2021. We want to know what's out there and we want to be prepared.

St. Louis filmmaker Paul Hibbard takes this modern world of jaded Americans as the subject of his new home invasion thriller, Some Visitors, a Hex After Dark award-winning short film that is currently making the rounds on the festival circuit, having shocked audiences at Grimmfest, Panic Fest, and Shockfest. Hibbard injects more cutting wit and clever curveballs into his 20+ minute flick than most features manage in 90 minutes.

Some Visitors' characters exist in a post-Genovese world, where the news is constantly spewing alerts about the latest rash of home invasion murders, and where no sane person would unlatch a lock for a stranger purporting to be in need of assistance. As someone who shares Hibbard's passion for the subgenre, I was eager to talk with him about this short-form mystery and its satisfying structure.

If Some Visitors were a house, you would say it has strong bones. You might also be tempted to sneak a peek inside, as I did. And if you're anything like me, you'll want to live in it for awhile despite the blood stains on the carpet. Why? Because the home invasion thriller allows us to confront a terrifying situation that we all dread.

After watching this haunting slice of domestic horror at a private screening, I was curious to ask its director where his mutual fascination with the home invasion film started. His response was not only astonishing but more than a little eye-opening. What it revealed was the extent to which mainstream American cinema has normalized the concept of burglary.

“What was the first home invasion film you remember watching?” I asked.

“Honestly, Home Alone is the first,” Hibbard said. “Even though it's not a horror, the brutality of how [Macauley Culkin's Kevin McCallister] handles the intruders sticks out. It's not mentioned much, but Home Alone should be considered a gateway horror/home invasion film.”

This was a revelation, as it forced me to revisit a film I hadn't seriously considered since childhood. In retrospect, the entire John Hughes/Chris Columbus family classic functions as something of an allegory about the loss of innocence. Granted, it's not as stark or nihilistic as Wes Craven's debut film (The Last House on the Left) or the Ingmar Bergman film (The Virgin Spring) on which it was based, but it shares the same concern with a child's loss of innocence and his descent into abject cruelty.

It is worth noting that for all of Kevin McCallister's inventive resourcefulness, he never once attempts to seek the help of adults or law enforcement. Instead, he sets a series of horrific traps for the film's pair of bumbling thieves, driving nails through the feet of one, while tarring and feathering the other, before ultimately lobbing full cans of paint at both of their skulls (a form of blunt force trauma that is presented in more realistic and grave detail in 2016's R-rated Christmas thriller, Better Watch Out). This is when the pre-pubescent boy isn't talking to creepy old men, committing petty theft, or plundering his older brother's stroke mags.

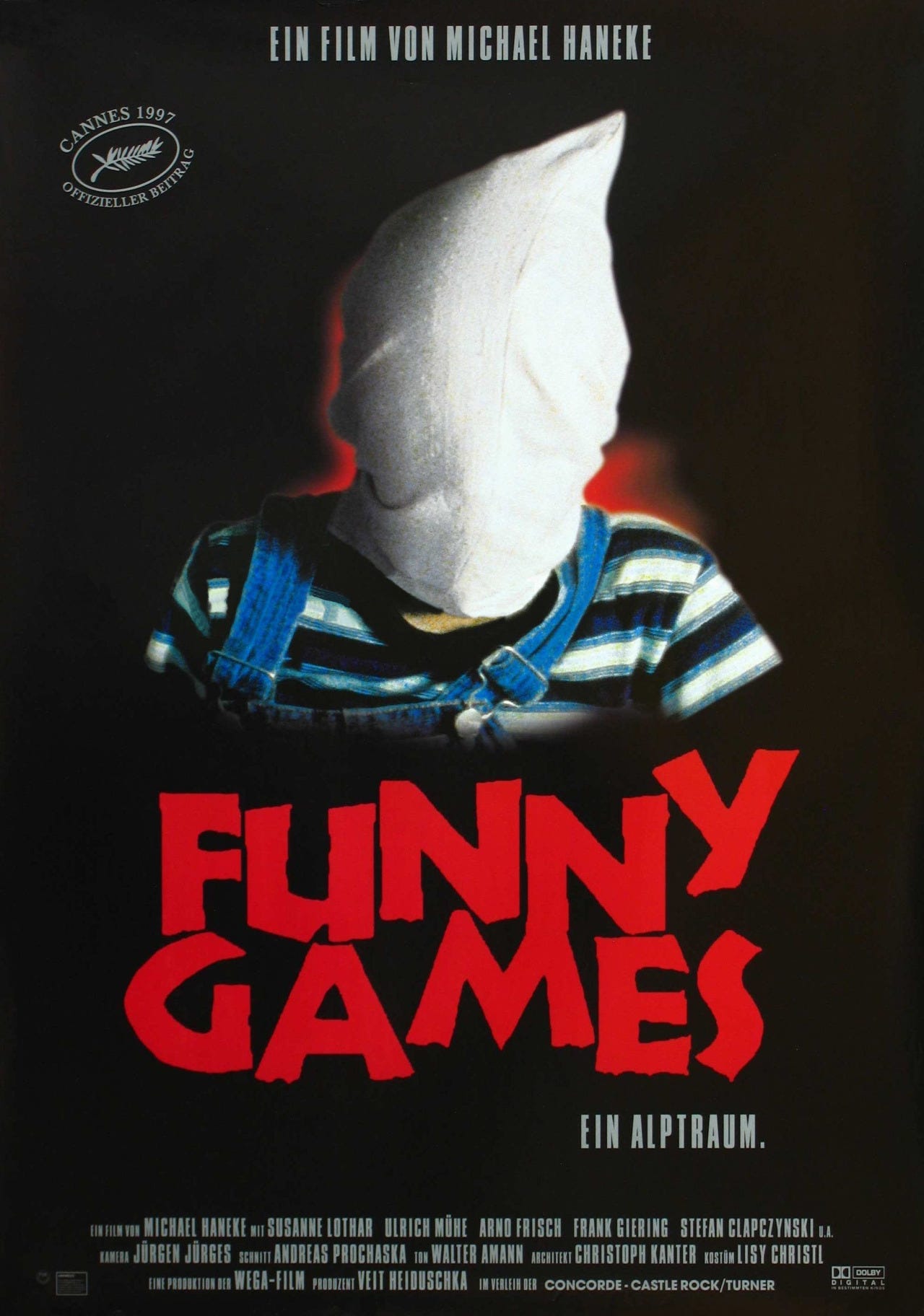

What Home Alone illustrates is American society's material insecurity and natural blood lust, a fact that Austrian art film auteur Michael Haneke played with in his own home invasion film, Funny Games, one of many films that influenced Some Visitors.

Haneke's fingerprints can be detected on several sequences in Some Visitors and Hibbard does nothing to conceal the debt he owes to Funny Games and its director. The vicious horror art film's presence is plain to see in the use of white gloves and the slightly more subtle deployment of a golf club late in the short's run time.

I ask Hibbard how he reconciles his own film's use of bloody and brutal violence in Some Visitors given the fact that Haneke has publicly referred to Funny Games as an indictment of audience complicity and on-screen violence in the American genre film.

“I think [Haneke]'s point of view in Funny Games is a point to be taken, and he's right, but the fact I'm so guilty of loving violence makes me enjoy Funny Games that much more, because he's calling me out. It creates a symbiotic relationship between him and me. And he's got me, and I love it, but I'm not changing.”

There is, however, a stronger influence at work here. When asked to name his top five home invasion recommendations for folks who want to do a deep dive into the genre, Hibbard picked Maury and Bustillo's Inside, Funny Games, Ils, Us, and Wait Until Dark. While the last two are a modern hype- driven throwback and a classic cat-and-mouse film anchored by the quietly menacing Alan Arkin, the first two out of three are examples of the early 2000s French horror renaissance.

As it turns out, the so-called Nouveau Extremity played a far more influential role in the development of Some Visitors than anything in the annals of the American canon.

“I was obsessed with European horror movies during the first decade of the 2000s,” Hibbard explained. “While American films were kind of stuck in a rut, producing endless Saw sequels...I was turning to ...the French Extremity movement and seeing what they were doing to push extremes. So, films like...Inside and Ils and the English film The Children dealt wth home invasions and human cruelty.”

As the horror landscape was choked by a glut of 80s nostalgia and legacy sequels, Hibbard struck out in his own direction. When it came time to take his own stab at the subgenre, the Missouri maestro wanted a different kind of nostalgia, one a little more obscure and more of his time.

“In terms of the violence, you could easily say this film is Inside and Funny Games put together,” Hibbard said. “... the former being the bigger influence, and the extreme violence is more taken from it. Funny Games is genius and has a point, but I don't know if its point is greater than what the French Extremity movement did, and it's all just part of the cinematic conversation.”

Conversation is something that plays a major role in Some Visitors, especially after the emotionally damaged Jessica (Jackie Kelly) reluctantly opens her door to Jeff (the mercurial Clayton Bury), a stranger who claims to have been in a car accident. Once Jessica agrees to help Jeff, the two end up engaging in a verbal folie à deux, one in which both are caught in a tangle of contradictions and ambiguities.

Without spoiling the raw meat of the flick, Some Visitors delivers a series of ah-ha about-faces and entertaining vagaries that are impressively timed for such a short piece. When I asked Hibbard how long it took to shoot, I was left genuinely gobsmacked by his answer.

“Four long, long days,” he said. “It was too tight a schedule because the house was pricey. We put long hours in. We ended up doing another half day doing insert shots a few months later.”

“It feels like a very intimate project,” I told him. “which I always love, where everything is sort of claustrophobic. Were you working with a small crew to achieve that claustrophobic look?”

“Very small,” Hibbard said. “Because we were at the height of COVID, but also because I truly believe small crews are best. There seems to be some macho aspects filmmakers flaunt about how big their crews are. Keep it small, it's better.”

I asked him where he found Clayton Bury, one of the film's two standouts.

“This guy gave me major Roger Bart vibes,” I said. “How did you work to calibrate that performance? Because his range within such a short runtime was pretty remarkable.”

“He's in LA now,” Hibbard explained. “but he was a major part of the St. Louis film scene for years, which is where [Some Visitors] is shot. He has been my leading man for years and this is the fifth movie we've done together. His range can go scary to dramatic to comedic in a flash.”

Hibbard and I talked about our mutual influences quite a bit, which inevitably led to the question of how to prepare to make a film of your own. As someone who is acutely aware of striking the right balance between influence and oversaturation, I shared my own experience with the Some Visitors director.

“When I made my first film, Of Bitches & Hounds, I showed my crew Eraserhead before we started shooting, and I was watching a lot of 70s and 80s horror art films before I did my Troma vampire film, Hemo. We would look at William Lustig's Maniac, Charles Kaufman's Mother's Day, Let's Scare Jessica to Death, and Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, and we shot for something with a similar sense of grime.”

I asked him if he rewatches any particular films when he's going into a new project or if he has a different approach to preparation.

“That is awesome,” he said. “And yes, I show them movies. Jackie...is a cinephile, so I don't need to show her anything. I just tell her the movie and she says she's got it. To prepare, Clayton and I watched Funny Games, Psycho, and Death Proof, to fill in his character.”

One of the more striking components of Some Visitors is its use of darkness, something which is absolutely essential to most home invasion films. It's not necessarily something the casual viewer would consider, but with the exception, perhaps, of Angst, the average home invasion film relies on darkness, just as an actual home invasion would rely on the same.

Some Visitors builds an equitable amount of tension through its use of darkness and light, drawing attention to the shafts of luminescence coming through windows, as if to remind the captive audience member that an escape could exist... if only we could make it to that light.

This occasional focus on exterior light sources also emphasizes the notion of the post-Genovese world, one where the neighbors are home to hear you scream, but they aren't about to risk their own lives to intervene on your behalf.

“The lighting worked really well,” I said. “The use of shadow was very effective at creating a sense of disorientation, where you're never quite sure exactly what is going on and who is getting injured. Did you have a game plan in terms of creating this atmosphere? Or was that something that you and your DP came up with on the fly?”

“It was half and half,” Hibbard explained. “We couldn't get into the location until it was time to shoot. So, it was impossible to completely plan it out, but he had a list of films that I wanted to emulate, Inside being one. And on set, it was a matter of getting that look but doing it on the fly while losing time. So, the end result, like with most indie film, is a compromise in the middle of getting what was planned the best you can.”

Despite my own theories on the subject, I was curious to hear Paul's thoughts about the public fascination with the home invasion genre.

“Why do you think audiences watch them? What do we get from it?”

The Show Me State showman suggested it works on two levels, one being the personal sense of intrusion.

“There's a structure of society people hold onto that our property is sacred and intruding on it is a major violation...It can also work in a grander political sense, making commentary on political things like privilege or immigration...In Inside, there is a whole subplot with news reports of immigrants in the background and the immigrant prisoner the police bring with them...Inside is really interesting because it's a lot more political than whats on the surface.”

Whether Hibbard means for Some Visitors to be read politically remains to be seen, though the viewer does get the impression that crime is something that is occurring too often and in everyone's backyard, an impression that is bolstered by the film's opening statistics. I told Hibbard that his killers' answer to why they do what they do was especially hardcore.

“In a way, it feels like the perfect reaction to all of these bullshit reboots that attempt to explain away the reasons for their villains' brutality. By stripping away the motivation or leaving motivation vague, this kind of film is so much scarier in my opinion. Would you agree? Is that something you were reacting to by putting that message in your killer's mouth?”

“Yes,” Hibbard agreed. “And without getting into spoilers, the way it's repeated later shows that the one who heard it was actually impressed. Probably the only thing that actually impressed them.”

Hibbard also advocated for horror films that force us to question our own culpability as consumers in the murder entertainment marketplace.

“Carrie is my favorite movie ever,” he said. “I hate the way it's viewed as a 'you go, girl!' movie. So many people don't realize the ones who hit her with blood are gone and no one is laughing at her. The whole gym is on her side. She's won. Nancy Allen and Travolta are probably forever suspended, if not arrested. Tommy is in love with her. Everyone sides with her.

“Every time I watch it, when she goes evil, I want to stop her. Even though this is what I wanted the whole movie. When it happens, I feel like I encouraged a monster. I'm trying my absolute hardest to make the audience feel similar, where they say, 'This is who we were rooting for?'”

Audience culpability aside, I had to admit that I was left greedy for more of Some Visitors once the chamber horror had concluded. This begged the question, “Are there any intentions of expanding on Some Visitors in the form of a feature film?”

“Yes,” Hibbard said without hesitation. “I have a feature script written with a cold open of another house attacked, more of a fight at the end, and longer conversations between the two [principal] characters, revealing things you only fully understand later.”

“What else do you have cooking?” I asked. “Is domestic horror a sandbox you hope to continue to play in?”

Hibbard said that his focus is on the development of a Some Visitors feature and a project entitled Wife of a Preacher Man. While the latter is not a horror film, he assured me that it plays with the same themes and has moments of extreme violence.

“If Some Visitors is my Funny Games, then Wife of a Preacher Man is my Piano Teacher, Hibbard suggested.

For those unfamiliar with Haneke's 2001 psychosexual adaptation of Elfriede Jelinek's icy and challenging novel, we can probably expect bad things to be inflicted on troubled people, which is where such acts belong – on the screen instead of in our own homes.

Some Visitors will be playing at Hysteria Fest at Arkadin Cinema in St. Louis from October 20 through the 22nd. Tickets are on sale for $10 here, or you can catch the film virtually through Shockfest starting December 10th.